How art and science fell into step for Salvatore Ferragamo.

Two gilded bronze feet – one from ancient Rome, the other by Henri Matisse – vie for attention with monkey pads, a ballerina’s arched instep and the tiny toes of a toddler taking his first steps.

I took a crash course about the human foot and its function at Equilibrium, a fascinating exhibition at the Salvatore Ferragamo Museum in Florence.

Given that I was hobbling with a bandaged and bloated instep after taking a tumble off my wedges in Capri at the Dolce & Gabbana couture show, I was particularly sensitive to the foot and its function.

But you don’t have to fall down a cliff to appreciate this erudite but edgy exhibition. I laughed at the sight of our predecessors, the primates, as hairy models plodding along in footprints found in Africa 3.6 million years ago.

I had a prick in my eyes when I saw the tiny calfskin shoes with non-slip soles which shoemaker Salvatore Ferragamo created in 1946 for his son Ferruccio, now president of the family business.

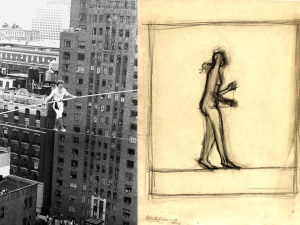

I also felt a lift of delight at figures swinging acrobatically in an empty space, like Alexander Calder’s mobiles and his circus inspirations. But I shivered at the sight and sound of the famous on film: the purposeful stride of John F Kennedy, the religious march of Mahatma Gandhi, and Adolf Hitler’s military goose-stepping.

Most of all, Stefania Ricci, the museum’s director and archivist, and art critic Sergio Risaliti,Equilibrium’s co-curators, should be applauded for the impressive art objects and references that they have brought together from museums around the world. They extend from an illustration of the journey from Dante’s The Divine Comedy, loaned from Florence’s Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, to Edgar Degas sculptures from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

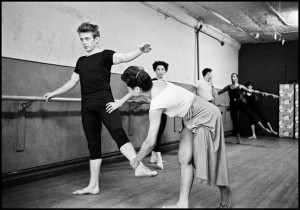

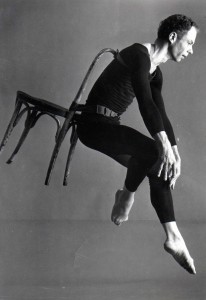

Especially poignant is the section on dance, where the delicacy of bare-footed Degas dancers or a fifteenth-century Raphael-style pen-and-ink drawing show us feet in a state of grace.

But the soul and the sole of shoes is, of course, Salvatore himself.

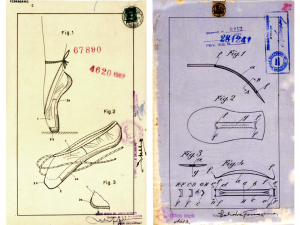

“He spent his life studying and learning about the human anatomy to improve his understanding of feet,” explained Stefania Ricci, as she showed me the different lasts the designer had worked on to further his scientific study of the arch of the foot.

With the intuitive understanding of an Italian who is surrounded by Renaissance architecture (where the premium arch takes the building’s weight), Ferragamo brought the same principle to shoes.

Marilyn Monroe, among other Hollywood stars, may have felt the benefit of Salvatore’s studies. But the volatile balance, especially in heels of different heights, was developed from scientific understanding into an art form.

The “shoemaker to the stars” understood that the entire weight of the body falls in a plumb line on the arch of the foot.

Looking at the fragility of Alberto Giacometti’s bronze figure of the Capsizing Man, I shared the artist’s impression of “the frailty of living beings, as if at any moment it took a formidable amount of energy for them to remain standing.”

In my previous post, I wrote about some of the absurdities of high-heeled fashion and asked why women were prepared to suffer to be “beautiful”.

The curators of the exhibition made me understand how difficult it is to create in footwear the “equilibrium” bestowed by nature – the muscles that move the skeleton and the neurons that control the anatomy.

But the scientific side of the exhibition is as light as a pair of fine leather court shoes. Those wanting to take the lesson further, can study the Equilibrium catalogue and its beautifully presented historical overview.

The fully illustrated book embraces the Neo-classical balance of Antonio Canova’s dancers and their “rhythms of grace”, the harsher visions of the distorted toes of American avant-garde dancer Merce Cunningham, and the implacably rigid carved amethyst Shoes for Departure (1991), by conceptual artist Marina Abramovic.

I hope this exhibition travels, because it is so much more meaningful than a mere display of footwear – just as Salvatore himself brought art, science and overall intelligence to his apparently humble craft.